Survey Methodology

This report is based on a survey conducted for Recreation Management by Stamats Inc., an independent research company. An e-mail was broadcast and respondents were invited to participate. From the launch of the survey on Sept. 27, 2022, to the closing of the survey on Oct. 10, 2022, 520 completed surveys were received from respondents with aquatic facilities (out of 741 total returns). The findings of this survey may be accepted as accurate, at a 95% confidence level, within a sampling tolerance of approximately +/- 4.28 percent.

After the extreme disruption to the industry in 2020 caused by the coronavirus pandemic, with effects still lingering in 2021, 2022 was the year that the aquatic industry began to return to normal operations, where it could. Still, the industry was faced with myriad challenges that prevented things from getting back on track entirely, including staff shortages exacerbated by the training lags of the pandemic shutdowns, as well as inflationary pressures that led to equipment and chemical cost increases.

After the extreme disruption to the industry in 2020 caused by the coronavirus pandemic, with effects still lingering in 2021, 2022 was the year that the aquatic industry began to return to normal operations, where it could. Still, the industry was faced with myriad challenges that prevented things from getting back on track entirely, including staff shortages exacerbated by the training lags of the pandemic shutdowns, as well as inflationary pressures that led to equipment and chemical cost increases.

In these pages, we’ll cover these broad industry trends, along with more specific data detailing how aquatic operations are faring in these turbulent times. We’ll give you the top-down view, looking at the responses of more than 500 aquatic industry professionals who completed the Aquatic Trends survey, and where appropriate, we’ll drill down into more specific data for various cohorts, including types of facilities (i.e., park districts, colleges, Ys, camps and more), whether pools are indoor or outdoor, as well as pools that spend a lot vs. a little on their operations.

Let’s start things off with a quick look at the demographics of the 520 survey respondents whose facilities include aquatic features. These facilities run anywhere from the smallest HOA pool up through community aquatic centers and college natatoriums to full-blown waterparks with rides, slides, wave pools and more.

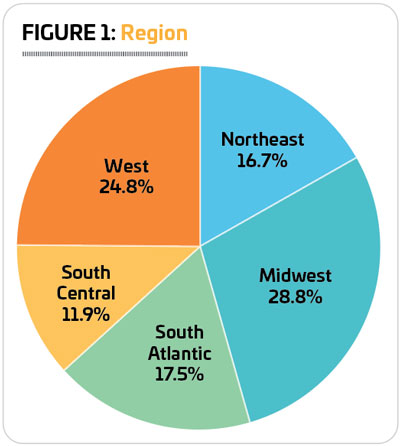

Respondents to the survey came from every region of the United States, but the largest cohort of respondents—28.8%—call the Midwest home. That includes Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, Ohio, South Dakota and Wisconsin. (See Figure 1.)

The West was the next most represented region, with 24.8% of survey respondents. This includes Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, Washington and Wyoming.

The West was the next most represented region, with 24.8% of survey respondents. This includes Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, Washington and Wyoming.

Some 17.5% of survey respondents were from the South Atlantic region. This includes Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Maryland, North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia, Washington, D.C., and West Virginia.

Some 16.7% of survey respondents make their home in the Northeastern states. This includes Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island and Vermont.

Finally, the South Central region was represented by 11.9% of respondents. This region includes Alabama, Arkansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Oklahoma, Tennessee and Texas.

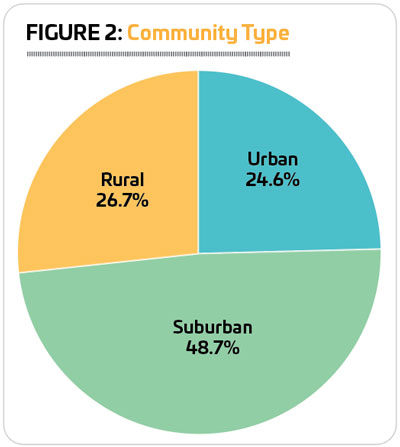

We also asked respondents to tell us what type of community they serve. Nearly half—48.7%—said they were located in suburban communities, with smaller numbers representing rural (26.7%) and urban (24.6%) communities. (See Figure 2.)

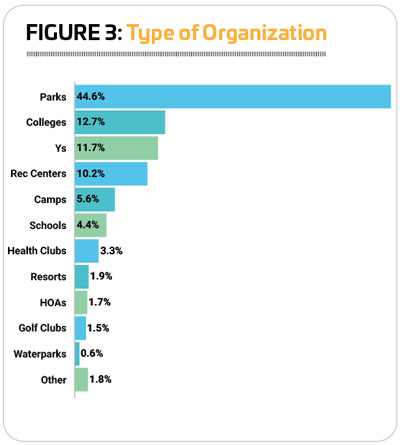

When it comes to the types of organizations covered, parks and recreation departments and districts were represented by the largest number of respondents, at 44.6%. They were followed by: colleges and universities (12.7%); YMCAs, YWCAs, JCCs and Boys & Girls Clubs (11.7%); community or private recreation and sports centers (10.2%); private or youth camps, campgrounds and RV parks (5.6%); schools and school districts (4.4%); sports, health and fitness clubs, racquet clubs, and medical fitness facilities (3.3%); resorts and resort hotels (1.9%); homeowners’ associations (1.7%); golf clubs and country clubs (1.5%); and waterparks (0.6%). Another 1.8% were from other types of organizations, including military installations and churches. (See Figure 3.)

Another 1.8% were from other types of organizations, including military installations and churches. (See Figure 3.)

(Where we consider data in terms of the type of organization in the following pages, we’ll be looking at parks, colleges, Ys, rec centers, camps and schools.)

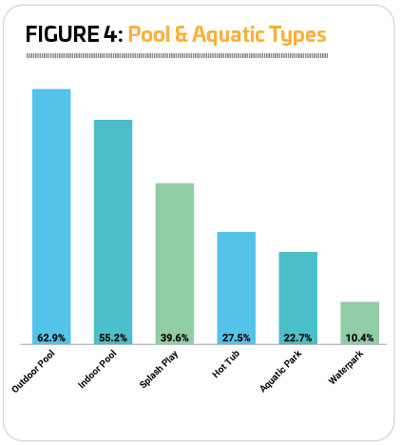

Whether it’s a zero-depth sprayground providing a place for neighborhood kids to cool off on hot summer days, a resort swimming pool with cabanas and a swim-up bar or a large aquatic park featuring multiple pools with waterslides and a lazy river, there’s a broad range of aquatic facilities out there. We asked respondents whether their facilities included a range of different facility types, including indoor and outdoor swimming pools, splash pads, hot tubs, aquatic parks (with a primary focus on swimming pools, and featuring other aquatic attractions) and waterparks (with a primary focus on rides and waterslides).

Outdoor swimming pools were the most common type of aquatic amenity, with 62.9% of respondents indicating they had at least one outdoor pool (and 8.8% had four or more outdoor pools!). That’s up from 58.8% in 2022. More than half of respondents (55.2%) had at least one indoor pool, up from 54.9% in 2022. Splash play areas were found among 39.6% of respondents’ facilities, up from 38.6% in 2022. And 27.5% had hot tubs, spas or whirlpools, down from 28.4% in 2022. (See Figure 4.)

The less common but more complex facilities—aquatic parks and waterparks—also saw slight increases in 2023. Some 22.7% of respondents said they currently have an aquatic park, up from 18.2%. And 10.4% currently have a waterpark, up just slightly from 10.2%).

Respondents from campgrounds were the most likely to report that they had at least one outdoor pool. Some 89.7% of camp respondents said they currently have at least one outdoor pool, up from 82.1% in 2022. They were followed by parks, where 80.2% of respondents had at least one outdoor pool (up from 75.1%), and rec centers, where 69.8% had at least one outdoor pool (down from 73.7%)

Respondents from campgrounds were the most likely to report that they had at least one outdoor pool. Some 89.7% of camp respondents said they currently have at least one outdoor pool, up from 82.1% in 2022. They were followed by parks, where 80.2% of respondents had at least one outdoor pool (up from 75.1%), and rec centers, where 69.8% had at least one outdoor pool (down from 73.7%)

Indoor pools were most common for respondents from schools. In fact, 100% of school respondents said they had at least one indoor swimming pool, up from 90.9% in 2022. They were followed by Ys (95.1%, up from 85.2%) and colleges and universities (87.9%, down from 94%).

Splash play areas were most commonly found at park facilities. Some 61.2% of park respondents said they had at least one splash play area, down from 63.3% in 2022. They were followed by rec centers (43.4%, up from 35.3%) and Ys (24.6%, down from 36.5%).

Y respondents were the most likely to report that they currently have at least one hot tub, spa or whirlpool. Some 52.5% of health club respondents have a hot tub, up from 42.9% in 2022. They were followed by colleges and universities (39.4%, up from 36.7%).

While less common, aquatic parks were featured at more than one-third of park respondents’ facilities. Some 34.5% of park respondents said they had an aquatic park, up from 30.8% in 2022.

The least common type of aquatic facility is waterparks, most commonly found in park respondents’ facilities (13.4% have a waterpark) or camp facilities (10.3%).

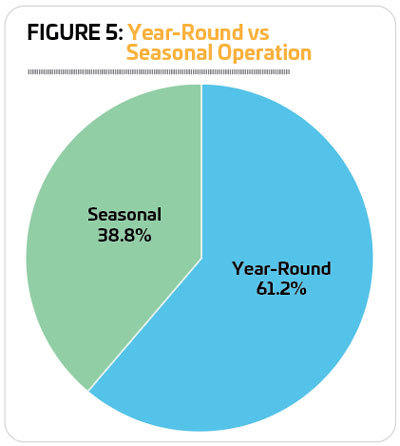

More than six in 10 respondents (61.2%) said that their aquatic facilities are open all year, while 38.8% said their aquatic operations are seasonal. (See Figure 5.)

More than six in 10 respondents (61.2%) said that their aquatic facilities are open all year, while 38.8% said their aquatic operations are seasonal. (See Figure 5.)

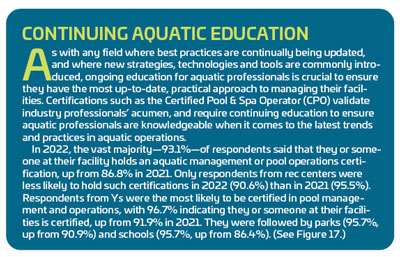

Year-round operations were most common for respondents from schools, colleges and Ys. The vast majority of these respondents said their aquatic facilities were open year-round, with 95.7% of school respondents, 95.5% of college respondents and 95.1% of Y respondents indicating they have year-round aquatic operations.

On the other end of the spectrum, camp respondents were the most likely to indicate that their operations are seasonal in nature. Just 10.3% of camp respondents said they operate year-round. They were followed by parks, where less than half (43.5%) have year-round operations. (See Figure 6.)

Not surprisingly, respondents who only have indoor swimming pools were highly likely to report that they operate year-round, compared with those who only have outdoor facilities. Among those who only operate indoor pools, 96.3% said those facilities are open year-round. This compares with 18.9% of those who only have outdoor pools.

Year-round operations were also associated with higher average operating budgets. Among respondents whose expenditures for fiscal 2021 were $500,000 or more, 77.4% said their facilities were open year round. That number fell to 65.3% for those with expenditures between $250,000 and $499,999; 60.7% for those with expenditures ranging from $100,000 to $249,999. Less than half (49%) of respondents whose fiscal 2021 expenditures were less than $100,000 had year-round operations.

May was the most common month for seasonal aquatic operations to begin. A majority (60.9%) of respondents with seasonal operations said they opened their aquatic facilities in May. Another 18.3% said their season opened in June. This trend is slightly different for camp facilities, where 50% of those with seasonal operations said they open for business in June, and 38.5% open in May.

May was the most common month for seasonal aquatic operations to begin. A majority (60.9%) of respondents with seasonal operations said they opened their aquatic facilities in May. Another 18.3% said their season opened in June. This trend is slightly different for camp facilities, where 50% of those with seasonal operations said they open for business in June, and 38.5% open in May.

September was the most common month for ending seasonal operations. Well over half (57.9%) of respondents with seasonal operations said their season comes to a close in September. Another 31.2% end their season in August.

Budget Issues

Editor’s Note: For this year’s survey, we changed the way we collect certain data. For this section, in previous years, respondents were asked to choose from a range of budget amounts (i.e., less than $100,000; $100,000 to $249,999; $250,000 to $499,999; etc.). For 2023’s report, we allowed respondents to select the exact dollar amount of their operat ing budget. Because of this, the results will look different this year from last, but this method will provide more precise results going forward.

ing budget. Because of this, the results will look different this year from last, but this method will provide more precise results going forward.

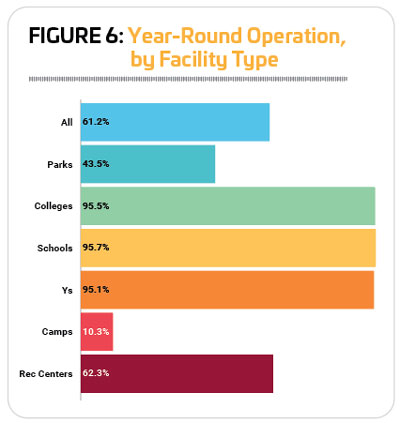

Respondents said their average operating cost for 2021 was $453,000. In 2022, they spent 9.1% more, $494,200, which is just a bit above the reported inflation of 7.75% for 2022 vs. 2021. Looking forward, aquatic respondents expect an increase of 8.8% from 2022’s average of $494,200 to an average of $537,850 in 2023. (See Figure 7.)

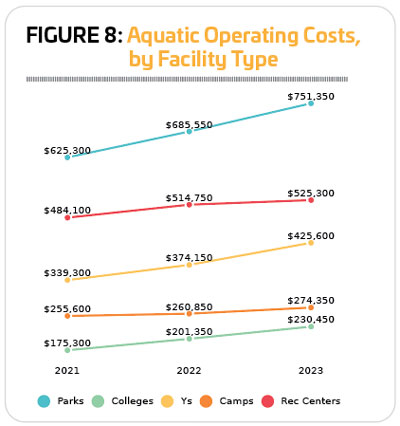

Respondents from parks reported the highest overall average operating cost, likely because parks were more likely than other respondents to be operating more than a single facility, and also were more likely to operate more complex (i.e., costly) facilities like aquatic parks. In fact, they were the only respondents whose operating costs were higher than the average reported for all respondents.

Parks spent 26.1% more in 2021 than the average for all respondents, with an average operating cost of $625,300. They were followed by rec centers, where respondents spent $484,100, 2.4% less than the average for all respondents; and Ys, where respondents spent $339,300, 31.6% less than the average for all respondents. The lowest average operating cost for 2021 was seen among colleges (which were highly likely to operate a single indoor swimming pool). They reported spending $175,300, 64.7% of the across-the-board average.

Respondents from rec centers, Ys and parks reported the sharpest increases to their average operating costs from 2021 to 2022. Rec centers reported a 14.9% increase, from an average of $175,300 in 2021 to $201,300 in 2022. They were followed by Ys, with a 10.3% increase from an average of $339,300 to $374,150; and parks, with a 9.6% increase from $625,300 to $685,550. Camps saw the smallest increase, with average operating costs rising just 2.1% from $255,600 in 2021 to $260,850 in 2022. (See Figure 8.)

Respondents from rec centers, Ys and parks reported the sharpest increases to their average operating costs from 2021 to 2022. Rec centers reported a 14.9% increase, from an average of $175,300 in 2021 to $201,300 in 2022. They were followed by Ys, with a 10.3% increase from an average of $339,300 to $374,150; and parks, with a 9.6% increase from $625,300 to $685,550. Camps saw the smallest increase, with average operating costs rising just 2.1% from $255,600 in 2021 to $260,850 in 2022. (See Figure 8.)

Rec centers, Ys and parks also reported the sharpest operating cost increases from 2021 to 2023, with costs rising more than 20% for each of these groups over the two-year period. Rec centers saw the greatest increase with a 31.5% rise from $175,300 in 2021 to $230,450 in 2023. Ys followed, reporting a 25.4% increase from $339,300 to $425,600. Park respondents reported a 20.2% increase, from $625,300 in 2021 to $751,350 in 2023.

Editor’s Note: The sample size of school respondents who answered budget-related questions was too small to provide accurate mean data. The median operating costs reported by school respondents for 2021 was $92,500. The median for 2022 was $90,000, and the median for 2023 was $160,000.

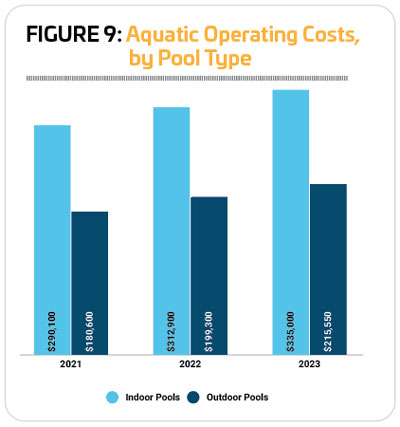

Indoor pools, being more likely to be open year-round and requiring proper ventilation and other equipment not necessary for outdoor pools, obviously come with higher operating costs. In fact, in 2021 respondents with indoor pools only spent 60.6% more on their annual operating costs than those with  outdoor pools only, $290,100 vs. $180,600. Indoor-only pools saw their operating costs rise 7.9% between 2021 and 2022, to an average of $312,900. This compares with a 10.4% increase for outdoor-only pools, to an average of $199,300. (See Figure 9.)

outdoor pools only, $290,100 vs. $180,600. Indoor-only pools saw their operating costs rise 7.9% between 2021 and 2022, to an average of $312,900. This compares with a 10.4% increase for outdoor-only pools, to an average of $199,300. (See Figure 9.)

Looking forward, those with indoor only pools projected a 7.1% increase to their average annual operating expenses from 2021 to 2022, reaching an average of $335,000. In that same period, those with outdoor pools only expect their operating costs to rise 8.2%, to an average of $215,550.

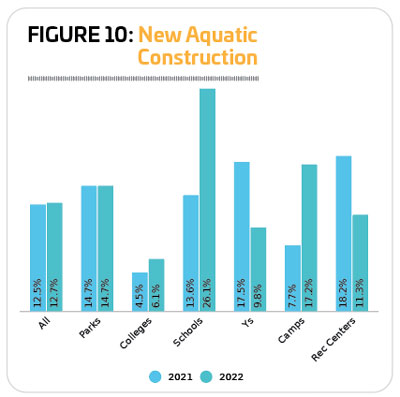

Similar numbers of respondents in 2022 said that they had built a new aquatic facility in the past three years, compared with 2021. Some 12.5% of respondents in 2021 said they had built new aquatic facilities, while in 2022 12.7% of respondents had built new facilities. They were led by respondents from schools, camps and parks. Some 26.1% of school respondents in 2022 said they had built a new aquatic facility over the past few years, up from 13.6% in 2021. Camps also saw an increase, with 17.2% in 2022 indicating they had built a new aquatic facility (up from 7.7% in 2021). Parks saw no change, with 14.7% of respondents in 2022 and in 2021 indicating they had built a new aquatic facility over the past three years. (See Figure 10.)

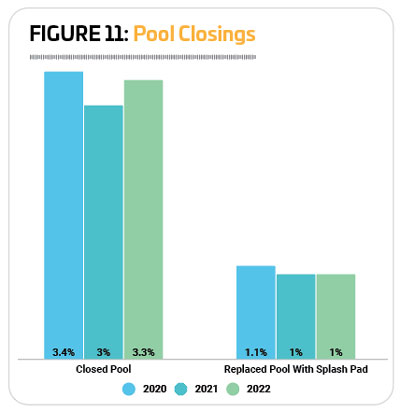

Despite budgetary pressures, very few respondents reported that they had closed aquatic facilities in 2022, with the numbers remaining virtually unchanged from 2021 and 2020. In 2022, 3.3% of aquatic respondents said they had permanently closed a pool without building a replacement, vir tually unchanged from 3% in 2021 and 3.4% in 2020. Another 1% said they had closed a pool and replaced it with a splash pad, unchanged from 1% in 2021 and 1.1% in 2020. (See Figure 11.)

tually unchanged from 3% in 2021 and 3.4% in 2020. Another 1% said they had closed a pool and replaced it with a splash pad, unchanged from 1% in 2021 and 1.1% in 2020. (See Figure 11.)

Respondents from colleges and universities were the most likely to report that they had permanently closed an aquatic facility without building a replacement over the past three years. Some 7.6% of college respondents indicated that they had done so. They were followed by Ys, where 4.9% said they had permanently closed an aquatic facility without building a replacement. Parks were the only respondents to report that they had replaced an existing swimming pool with a splash pad. Some 2.2% of park respondents said they had replaced a swimming pool with a splash pad over the past three years.

Water & Resource Management

We asked survey respondents to tell us about various types of systems they rely on to maintain good water quality at their aquatic facilities, from different types of filters to automation systems and secondary disinfection.

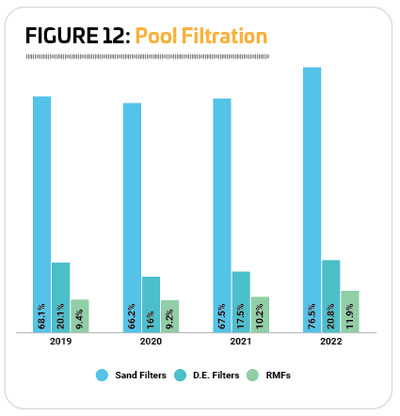

Sand filters continue to be the most dominant method of pool filtration. In fact, more respondents in 2022 (76.5%) said they used sand filters than in 2021 (67.5%), 2020 (66.2%) or 2019 (68.1%). Diatomaceous earth, or D.E., filters were also more commonly used in 2022, with 20.8% of respondents indicating they use them, up from 17.5% in 2021. Regenerative media filters (RMFs) also saw a slight increase in usage, with 11.9% of respondents using them in 2022, compared with 10.2% in 2021. (See Figure 12.)

A majority (84.6%) of respondents reported that they currently use chlorination systems at their facilities, up from 80% in 2021. Another 7.8% said they rely on bromination systems, up from 6.9% in 2021, but still down from 11.7% in 2020. Nearly four in 10 (38.4%) said they currently use a tablet chlorination system (up from 36.5%), and 3% are using salt chlorine generators (down from 6.7%).

A majority (84.6%) of respondents reported that they currently use chlorination systems at their facilities, up from 80% in 2021. Another 7.8% said they rely on bromination systems, up from 6.9% in 2021, but still down from 11.7% in 2020. Nearly four in 10 (38.4%) said they currently use a tablet chlorination system (up from 36.5%), and 3% are using salt chlorine generators (down from 6.7%).

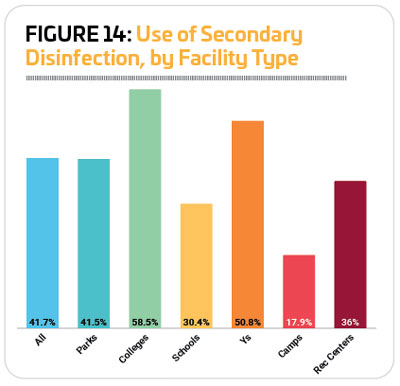

Secondary disinfection is recommended by the Model Aquatic Health Code (MAHC) as a way to improve water quality and better prevent recreational water illnesses. Given this, it should come as no surprise that the number of respondents who employ some form of secondary disinfection at their facilities has been on the rise. Some 41.7% of respondents said they currently employ some form of secondary disinfection at their facilities, up from 35.2% in 2021, and 35.8% in 2020.

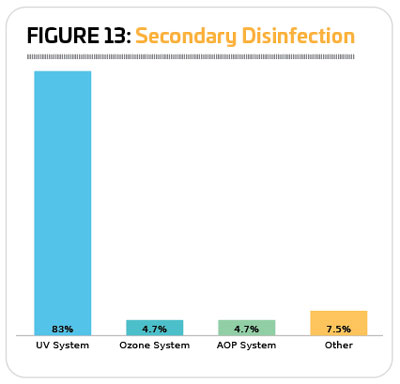

UV systems continue to dominate as the most common form of secondary disinfection by far. Some 83% of those who use secondary disinfection said they currently rely on UV systems, down from 88.5% in 2021, but up from 78.8% in 2020. Another 4.7% are using ozone systems (down from 6.9%), and another 4.7% are using AOP (advanced oxidation process) systems, up from 2.9%. Another 7.5% said they use some other form of secondary disinfection. (See Figure 13.)

Colleges and universities were the most likely to use secondary forms of disinfection. Some 58.5% of college respondents said they do so. They were followed by Ys, where 50.8% of respondents said they currently rely on a secondary form of disinfection. Camp respondents were the least likely to use s econdary disinfection, with 17.9% reporting they do so, up from 15.4% in 2021. (See Figure 14.)

econdary disinfection, with 17.9% reporting they do so, up from 15.4% in 2021. (See Figure 14.)

Respondents who spent more annually on their operations were much more likely to report that they use secondary disinfection at their facilities. Some 69.5% of those whose operating costs are more than $500,000 a year said they currently use secondary disinfection, up from 60.6% in 2021. For those with annual costs between $250,000 and $499,999, 41.1% are using secondary disinfection, up from 40%. Some 35.1% of those with costs between $100,000 and $249,999 use secondary disinfection, while 28.3% of those whose operating costs are less than $100,000 use secondary disinfection systems.

Respondents with indoor pools only are far more likely to use secondary disinfection than those with outdoor-only pools. Some 38% of those with indoor pools only said they currently use secondary disinfection, up from 36.7% in last year’s report. Just 8.3% of those with outdoor pools only said they rely on secondary disinfection, up from 5%.

Looking forward, 16.7% of respondents said they had plans to add new systems or update existing systems at their aquatic facilities over the next three years, up from 13.1% in 2021. Respondents from schools and rec centers were the most likely to be planning to add new systems or update their existing systems. Some 26.1% of school respondents and 24.5% of rec center respondents said they had such plans.

RMFs continue to be the most commonly planned filtration system upgrade. Some 25.3% of those with plans for updates said they would be adding RMFs, up from 20.9% in 2021. An other 17.2% were planning to add sand filters (up from 9%), and 14.9% were planning to add D.E. filters (down from 16.4%). Respondents from Ys (40.5%), rec centers (38.5%) and parks (31.4%) were the most likely to indicate they would be adding RMFs.

other 17.2% were planning to add sand filters (up from 9%), and 14.9% were planning to add D.E. filters (down from 16.4%). Respondents from Ys (40.5%), rec centers (38.5%) and parks (31.4%) were the most likely to indicate they would be adding RMFs.

Like regenerative media filtration, salt chlorine generators are also a relatively new technology that is seeing increased adoption. Some 24.1% of respondents to this year’s survey who had plans for upgrades said they would be adding salt chlorine generation, up from 13.4% in 2021. Rec centers (30.8%) and parks (20%) were the most likely to have such plans.

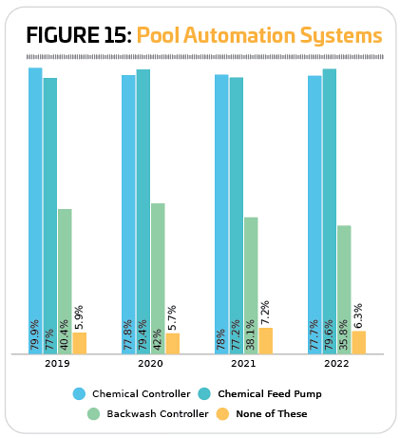

Automation systems can help manage water balance, maintaining a continual stream of chlorine and using other methods to measure and maintain water quality. Only 6.3% of respondents in 2022 said they have deployed no types of controllers on their pools, down from 7.2% in 2021. Most common in 2022 were chemical feed pumps, used by 79.6% of respondents (up from 77.2%). Another 77.7% use chemical controllers, representing virtually no change from 78% in 2021. And 35.8% use backwash controllers, down slightly from 38.1% in 2021. (See Figure 15.)

More than half (55.6%) of respondents to the Aquatic Trends survey said they deploy strategies and tools to conserve resources at their facilities. This number has fallen fairly significantly since 2019, when 71% of respondents said they were conserving resources. Energy conservation was most common, with more than one-third (34.4%) of respondents indicating they have systems and strategies in place to reduce their energy consumption, down from 47.5% in 2021. Another 31.2% aim to conserve chemicals (down from 49.2%), and 24% have systems and strategies in place to co nserve water (down from 42.6%).

nserve water (down from 42.6%).

Respondents from rec centers and colleges were the most likely to report that they currently use strategies and systems to conserve water, energy or chemicals at their facilities. Some 69.8% of rec center respondents said they conserve resources, down from 75% in 2021. And 69.7% of college respondents said they conserve resources, down from 75.8%. More than half of respondents from parks (54.7%) and schools (52.2%) also said they have strategies and systems in place to conserve resources. Camps were the least likely to do so, with just over a third (34.5%) indicating they conserve resources. They were followed by Ys, at 41%.

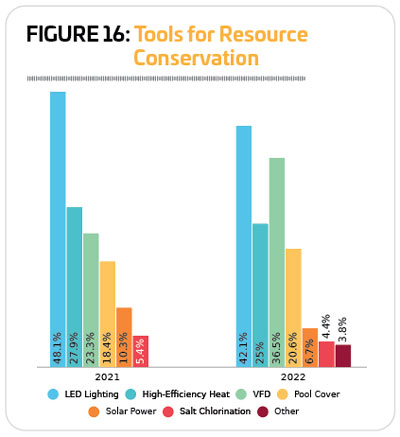

Many of the tools commonly used to conserve energy, chemicals and water at aquatic facilities, such as LED lighting and high-efficiency heaters, saw slightly less use in 2022 than in 2021. LED lighting is still the most commonly used tool covered by the survey, with 42.1% of respondents in 2022 indicating they used it, down from 48.1% in 2021. LED lighting was followed by variable frequency drives and pumps, which saw increased deployment in 2022. Some 36.5% of 2022 respondents said they used VFDs to conserve resources at their facilities, up from 23.3%. Pool covers also saw a slight increase in usage, from 18.4% of respondents in 2021 to 20.6% in 2022. (See Figure 16.)

Pool Equipment Expands Program Potential

As aquatic facilities have sought to expand their programming beyond learn-to-swim and water safety, many have found that simple additions of equipment make for big opportunities. Whether your pool is a classic rectangle begging for a little more fun, or you’ve got a complex aquatic park, the right equipment is key to helping you support safety, recreational and competitive programming, the comfort of swimmers and patrons and much more.

The equipment most commonly found at respondents’ facilities includes lifeguard stands (84% of respondents have lifeguard stands), lane lines (80.8%), pool lifts or other accessibility equipment (69%), pool exercise equipment (53.8%) and starting platforms (52.7%). Beyond that, there is a wide range of equipment found at aquatic facilities, supporting competitive events, family recreation, health and wellness, and so much more.

Here is a list of in-pool and on-the-deck equipment commonly found among respondents’ facilities:

- Lifeguard Stand: 84%

- Lane Lines: 80.8%

- Pool Lift or Other Accessibility Equipment: 69%

- Pool Exercise Equipment: 53.8%

- Starting Platforms: 52.7%

- Diving Boards: 51.7%

- Shade Structures: 46%

- Pool Slides: 44.8%

- Zero-Depth Entry: 42.5%

- Water Basketball Equipment: 34%

- Scoreboard: 27.9%

- Water Polo Equipment: 23.5%

- Teaching Platform: 21.2%

- Pool Inflatables: 19.6%

- Water Volleyball Equipment: 18.7%

- Water Playground: 17.9%

- Swim Platform: 15.2%

- Swim Wall or Pool Bulkhead: 13.5%

- Lazy River: 13.3%

- Poolside Climbing Wall: 10.6%

- Diving Platforms: 9.8%

- Poolside Cabanas: 8.7%

- Lily Pads/Water Walk: 6%

- Underwater Treadmill or Bike: 3.8%

- Pool Obstacle/Ninja Course: 3.1%

- Wave Pool: 2.1%

- River Raft Ride: 1.0%

- Surf Machine: 0.8%

- Water Coaster: 0.6%

Many items were more commonly used in 2022 than in 2021. Those that saw growth of at least five percentage points from 2021 to 2022 include: shade structures (up 7.3 percentage points; shade structures also saw a significant jump from 2020 to 2021); teaching platforms (up 7.2); starting platforms (up 6.7); swim platforms (up 6.1); lifeguard stands (up 5.5); diving boards (up 5.1); and pool lifts or other accessibility equipment (up 5 percentage points).

Many items were more commonly used in 2022 than in 2021. Those that saw growth of at least five percentage points from 2021 to 2022 include: shade structures (up 7.3 percentage points; shade structures also saw a significant jump from 2020 to 2021); teaching platforms (up 7.2); starting platforms (up 6.7); swim platforms (up 6.1); lifeguard stands (up 5.5); diving boards (up 5.1); and pool lifts or other accessibility equipment (up 5 percentage points).

Respondents from parks were more likely than others to include: pool slides, water coasters, river raft rides, lily pads/water walks, diving boards, wave pools, water playgrounds, zero-depth entry, lazy rivers, shade structures and surf machines.

College respondents were more likely than others to include: diving platforms, underwater treadmills or bikes; water polo equipment, water basketball equipment, water volleyball equipment, and swim walls or pool bulkheads.

School respondents were the most likely to include scoreboards and swim platforms.

Respondents from Ys were the most likely to include: starting platforms, lane lines, pool exercise equipment, teaching platforms, pool lifts and accessibility equipment, and lifeguard stands.

Respondents from camps were more likely than others to feature pool inflatables.

Finally, respondents from rec centers were the most likely to include poolside climbing walls, as well as obstacle or ninja courses.

Respondents in 2022 were much more likely to report that they had plans to add features at their facilities than in previous years. Some 40.2% of respondents said they had such plans, up from 24.3% in 2021 and 26.3% in 2020. This number is even a substantial jump from the pre-pandemic number in 2019, 32%. Respondents from schools, rec centers and parks were the most likely to be planning to add features. Some 47.8% of school respondents, 45.3% of rec center respondents and 42.7% of park respondents said they would be adding features at their facilities over the next three years. Respondents from colleges were the least likely to be planning to add features at their facilities. (See Figure 18.)

Respondents in 2022 were much more likely to report that they had plans to add features at their facilities than in previous years. Some 40.2% of respondents said they had such plans, up from 24.3% in 2021 and 26.3% in 2020. This number is even a substantial jump from the pre-pandemic number in 2019, 32%. Respondents from schools, rec centers and parks were the most likely to be planning to add features. Some 47.8% of school respondents, 45.3% of rec center respondents and 42.7% of park respondents said they would be adding features at their facilities over the next three years. Respondents from colleges were the least likely to be planning to add features at their facilities. (See Figure 18.)

The 10 most commonly planned additions at aquatic facilities include:

1. Shade structures (planned by 30.1% of those who will be adding features, up from 19.4% in 2021)

2. Poolside climbing walls (25.4%, down from 28.2%)

3. Pool obstacle/ninja courses (22.5%, up from 12.1%)

4. Poolside cabanas (19.6%, up from 10.5%)

5. Pool inflatables (16.7%, down from 17.7%)

6. Water volleyball equipment (16.3%, up from 8.1%)

7. Water playgrounds (14.8%, up from 11.3%)

8. Underwater treadmills or bikes (14.8%, up from 12.9%)

9. Pool slides (14.4%, down from 15.3%)

10. Pool exercise equipment (14.4%, up from 12.1%)

Respondents from parks were the most likely to be planning to add diving platforms, lane lines, poolside cabanas, surf machines, water polo equipment, and scoreboards.

Respondents from parks were the most likely to be planning to add diving platforms, lane lines, poolside cabanas, surf machines, water polo equipment, and scoreboards.

School respondents were the most likely to be planning to add pool lifts and accessibility equipment, water basketball equipment, and swim platforms.

Respondents from Ys were the most likely to be planning to add pool slides, water coasters, river raft rides, pool obstacle or ninja courses, diving boards, starting platforms, pool exercise equipment, underwater treadmills or bikes, teaching platforms, zero-depth entry, lazy rivers, and swim walls or pool bulkheads.

Respondents from camps were the most likely to be planning to add poolside climbing walls, pool inflatables, wave pools, water playgrounds, shade structures, lifeguard stands, and water volleyball equipment.

Finally, rec center respondents were the most likely to be planning to add lily pad or water walks.

Programming

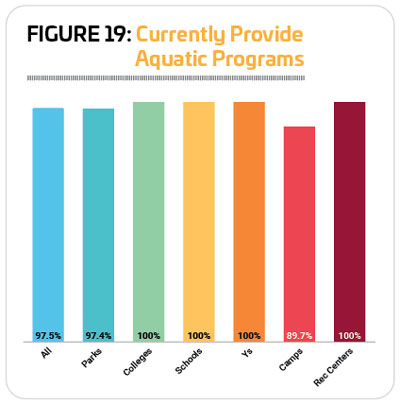

While there are pools and aquatic facilities that do not offer aquatic programming (such as most splash pads, for example), the vast majority of respondents to the Aquatic Trends survey said that they do provide some kind of programming at their aquatic facilities, from swimming lessons and aquatic safety to swim meets and competitions, aquatic exercise, dive-in movies and more. Some 97.5% of respondents in 2022 said they currently provide programming at their facilities, up from 96% in 2021 and 95.9% in 2020. A full 100% of respondents from colleges, schools, Ys and rec centers said they currently feature aquatic programs at their facilities. While not all parks and camps provide programs, the vast majority do, with 97.4% of park respondents and 89.7% of camp respondents indicating that they do offer aquatic programming at their facilities. (See Figure 19.)

While there are pools and aquatic facilities that do not offer aquatic programming (such as most splash pads, for example), the vast majority of respondents to the Aquatic Trends survey said that they do provide some kind of programming at their aquatic facilities, from swimming lessons and aquatic safety to swim meets and competitions, aquatic exercise, dive-in movies and more. Some 97.5% of respondents in 2022 said they currently provide programming at their facilities, up from 96% in 2021 and 95.9% in 2020. A full 100% of respondents from colleges, schools, Ys and rec centers said they currently feature aquatic programs at their facilities. While not all parks and camps provide programs, the vast majority do, with 97.4% of park respondents and 89.7% of camp respondents indicating that they do offer aquatic programming at their facilities. (See Figure 19.)

The following are the types of programs covered in the survey and their prevalence among respondents’ offerings:

- Lifeguard Training: 83.5%

- Learn-to-Swim Programs: 83.3%

- Leisure Swim Time: 81.5%

- Lap Swim Time: 78.8%

- Aquatic Aerobics: 66.7%

- Birthday Parties: 62.9%

- Water Safety Training: 62.1%

- Youth Swim Teams: 57.5%

- Swim Meets & Other

- Competitions: 54.8%

- School Swim Teams: 38.8%

- Water Walking: 36.2%

- Aquatic Programs for Those

- With Physical Disabilities: 32.3%

- Aquatic Programs for Those With Developmental Disabilities: 31.2%

- Dive-In Movies: 23.8%

- Adult Swim Teams: 23.8%

- Aqua-Yoga & Other Balance Programs: 21.7%

- Aquatic Therapy: 19.8%

- Diving Programs & Teams: 18.1%

- Water Polo: 17.3%

- Doggie Dips: 13.7%

- Collegiate Swim Teams: 11.3%

- Ninja Competitions: 0.4%

Programs that saw an increase of at least five percentage points over 2021 include: leisure swim time (up 7.4 percentage points); water safety training (up 7.1); water walking (up 6.9); swim meets and other competitions (up 6.6); lifeguard training (up 6.4); adult swim teams (up 6.3); lap swim time (up 6.3); birthday parties (up 5.7); and learn-to-swim programs (up 5.6).

Programs that saw an increase of at least five percentage points over 2021 include: leisure swim time (up 7.4 percentage points); water safety training (up 7.1); water walking (up 6.9); swim meets and other competitions (up 6.6); lifeguard training (up 6.4); adult swim teams (up 6.3); lap swim time (up 6.3); birthday parties (up 5.7); and learn-to-swim programs (up 5.6).

As usual, respondents from Ys were the most likely to offer a broad range of program opportunities. Respondents from Ys were more likely than others to offer: learn-to-swim programming; youth swim teams; adult swim teams; programs for those with physical disabilities; programs for those with developmental disabilities; aquatic aerobics; water walking; leisure swim time; aquatic therapy; ninja competitions; water safety programs; and lifeguard training.

Park respondents were more likely than others to offer doggie dips. Respondents from colleges were the most likely to offer collegiate swim teams, lap swim time, diving programs and teams, and water polo. School respondents were the most likely to offer school swim teams, and swim meets and competitions. And finally, rec center respondents were the most likely to include aqua-yoga and other balance programs, birthdays and dive-in movies.

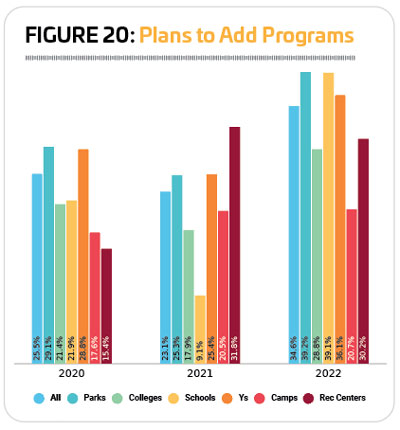

Respondents in 2022 were far more likely than respondents to the 2021 survey to report that they had plans to add programs at their facilities over the next three years. Well over a third (34.6%) said they had plans to add aquatic programming, up from 23.1% in 2021 and 25.5% in 2020.

Respondents from parks and schools were the most likely to indicate that they would be adding programs at their aquatic facilities. Some 39.2% of park respondents and 39.1% of school respondents said they had such plans. More than one-third of Ys (36.1%) were also planning to add programs. Camp respondents were the least likely to have plans to add programs at their aquatic facilities over the next few years, though more than one-fifth (20.7%) of camp respondents did have such plans. Respondents from rec centers were the only cohort that was less likely to have plans to add programs in 2022 (30.2%) than in 2021 (31.8%). (See Figure 20.)

The top 10 most commonly planned program additions include:

1. Programs for those with physical disabilities (planned by 38.9% of

those who will be adding programs, up from 28.8% in 2021)

2. Programs for those with developmental disabilities (33.9%, up from 28.8%)

3. Dive-in movies (33.3%, up from 23.7%)

4. Aqua-yoga and other balance programs (28.3%, no change from 28%)

5. Aquatic aerobics (23.9%, down from 24.6%)

6. Aquatic therapy (21.1%, up from 11.9%)

7. Water walking (15.6%, up from 9.3%)

8. Youth swim teams (15.6%, down from 16.1%)

9. Birthday parties (15%, up from 13.6%)

10. Learn-to-swim programs (15%, down from 19.5%)

Children might be the most common audience for learn-to-swim programming, but in fact, many facilities reach out to a wider audience with learn-to-swim opportunities—a smart strategy given that the opportunity to learn isn’t always available for children. We asked the 83.3% of respondents who offer learn-to-swim programs some further questions about the audience they reach with their programs.

Children might be the most common audience for learn-to-swim programming, but in fact, many facilities reach out to a wider audience with learn-to-swim opportunities—a smart strategy given that the opportunity to learn isn’t always available for children. We asked the 83.3% of respondents who offer learn-to-swim programs some further questions about the audience they reach with their programs.

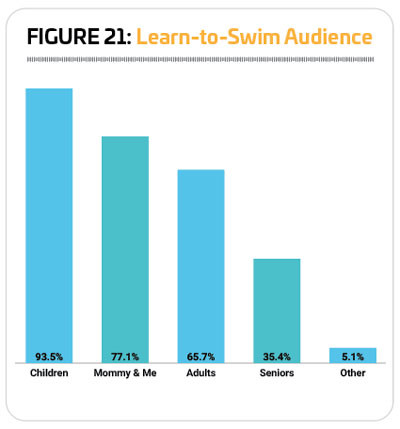

There was little change in the typical audience for learn-to-swim programs from 2021 to 2022. The vast majority (93.5%) of those who currently provide learn-to-swim programs said they have programs for children ages 17 and younger, down from 94.8% in 2021 and 96% in 2020. Another 77.1% said they provide learn-to-swim programs for parents and babies or toddlers, such as mommy (or daddy) and me classes, up from 71.9% in 2021. Nearly two-thirds (65.7%) said they provide learn-to-swim programs for adults 18 and up, representing virtually no change from 2021, and 35.4% offer swim lessons for seniors, down slightly from 36.1% in 2021. (See Figure 21.)

Some audiences tend to be left out when it comes to learn-to-swim opportunities, with economic as well as racial disparities having a heavy impact on who does and does not learn to swim. A 2017 USA Swimming report found that 79% of children in low-income families have little to no swimming ability, and 64% of black children, and 45% of Hispanic children have little to no swimming ability, compared with 40% of white children. Various grants and programs across the country have made it their mission to remove the barriers to learn-to-swim program for minorities and low-income communities. In addition, there are programs that aim to work with people who have a fear of the water, helping them overcome their phobias and learn to swim.

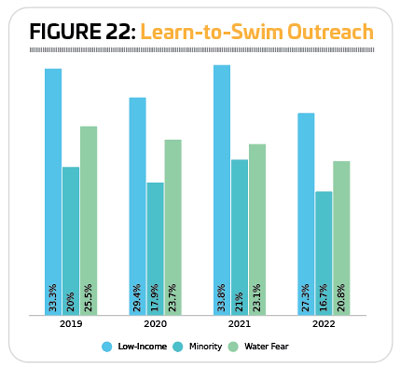

The number of respondents to the Aquatic Trends survey involved in these types of programs has fallen somewhat over the past several years. Some 27.3% of respondents in 2022 said they were involved in outreach to low-income patrons, down from 33.8% in 2021. Another 16.7% engage in minority outreach, down from 21% in 2021. And 20.8% offer learn-to-swim programs aimed at helping people overcome their fear of the water, down from 23.1% in 2021. (See Figure 22.)

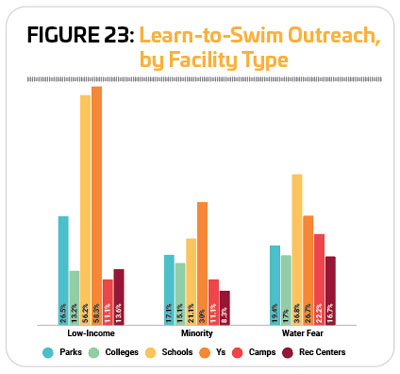

When it comes to outreach to low-income and minority audiences for learn-to-swim opportunities, Ys lead the way, with 58.3% of Y respondents involved in low-income outreach, and 30% involved in minority outreach. More than half of school respondents (56.2%) also were involved in low-income outreach programs. Schools were the most likely to be involved in programs to help people overcome their fear of the water. Some 36.8% of school respondents said they had programs aiming to address water fears. They were followed by Ys, where 26.7% of respondents had programs to help people overcome their fear of the water and learn to swim. (See Figure 23.)

Water Safety

Water safety training, provided by 62.1% of respondents, is an important way to ensure community members have the water skills they can take anywhere, from the park district to the backyard, boating and beyond. But drowning prevention is one of the essentials of operating an aquatic facility, and to help with this, the vast majority of facilities rely on lifeguards.

water skills they can take anywhere, from the park district to the backyard, boating and beyond. But drowning prevention is one of the essentials of operating an aquatic facility, and to help with this, the vast majority of facilities rely on lifeguards.

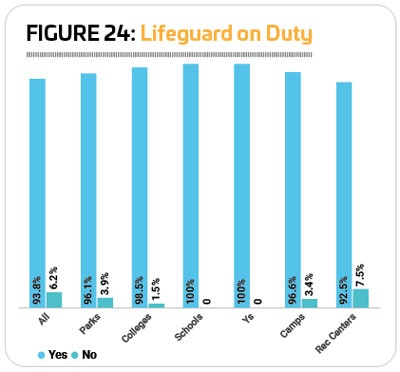

The majority of respondents—93.8%

—said a lifeguard is on duty at least some of the time during their operating hours, up from 91.5% in 2021 and 90.6% in 2020. Some 84.4% said a lifeguard is on duty at all times the facility is open (up from 79.5% in 2021), while 9.4% said a lifeguard is on duty during at least some hours of operation. Just 6.2% said a lifeguard is never on duty at their facilities, down from 8.5% in 2021 and 9.4% in 2020.

All 100% of the respondents from Ys and from schools said they have a lifeguard on duty at least some of the time, with 96.5% of Ys and 82.6% of schools indicating that a lifeguard is always on duty when their aquatic facilities are open. Respondents from rec centers and parks were the least likely to have a lifeguard on duty, though the vast majority of each group (92.5% of rec center respondents and 96.1% of park respondents) said a lifeguard is on duty at least some of the time. (See Figure 24.)

Many facilities take a layered approach to drowning prevention, and while having a lifeguard on duty is the most essential practice in this regard, other methods can provide an extra layer of protection for swimmers. When it comes to drowning prevention, the methods most often deployed by respondents include:

Lifeguard on Duty: 92.3%, up from 91.5% in 2021

Lifeguard on Duty: 92.3%, up from 91.5% in 2021- Life Preservers Required for Less-Skilled Swimmers: 40.9%, down from 49%

- Video or Other In-Pool System for Detecting Swimmers in Trouble: 5.2%, virtually unchanged from 5.3%

- Safety Device That Sounds an Alarm When Submerged: 2.7%, down from 4.5%

- Other: 6.5%

- None: 3.7%, down from 5.9%

The Model Aquatic Health Code

First released in the summer of 2014, the Model Aquatic Health Code (MAHC) was established by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC) to help state and local government officials develop and update their pool codes based on the most up-to-date science and agreed-on best practices.

The codes that govern pool operations, including guidance on how and how often to test the water, how facilities are built, how chemicals are used to protect swimmers from disease and so on, have traditionally been created at the local and state level. Because of this, a wide variety of regulations exists across the country. The MAHC aims to establish standardized guidance based on industry consensu s around best practices. So, while local and state governments are still creating their own codes, they can do so more easily using the MAHC.

s around best practices. So, while local and state governments are still creating their own codes, they can do so more easily using the MAHC.

What’s more, the MAHC is updated on a regular basis, which means those who use the code to help establish their own local regulations can easily stay on top of the latest guidance. The current edition of the code was released in 2018, and is the third edition of the code. The fourth edition was delayed slightly due to the coronavirus pandemic, but updates are under way, and the updates are expected to be released soon.

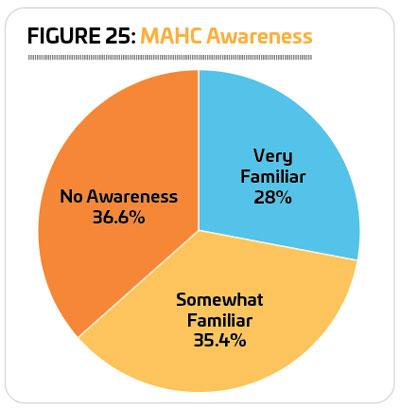

This year’s report shows a jump in the number of respondents who are familiar with the MAHC. Nearly two-thirds (63.4%) of respondents in 2022 said they are familiar with the MAHC, up from 56.4% in 2021. Some 28% said they are very familiar with the MAHC (up from 20.3%), and 35.4% are somewhat familiar (down from 36.1%). Still, more than one-third (36.6%) of respondents are still unfamiliar with the MAHC. (See Figure 25.)

When it comes to ensuring that the MAHC is updated on a regular basis, the Council for the Model Aquatic Health Code (CMAHC), created in 2013, acts as a clearinghouse for input and advice. CMAHC members take part in the process of updating the code and their input is considered as the CDC revises and releases the next edition. The next CMAHC “Vote on the Code” Conference is planned for 2023, though the dates and location have not yet been released.

Just 9.2% of respondents to the Aquatic Trends survey said t hey participate in the CMAHC, up from 6.4% in 2021. Just 1% are on the committee itself, and 8.2% said they have provided input.

hey participate in the CMAHC, up from 6.4% in 2021. Just 1% are on the committee itself, and 8.2% said they have provided input.

The code is not a federal law, which means government agencies can choose whether to adopt it at all, whether to use all of the MAHC or just part of it, or whether to modify all or part of it to fit their needs.

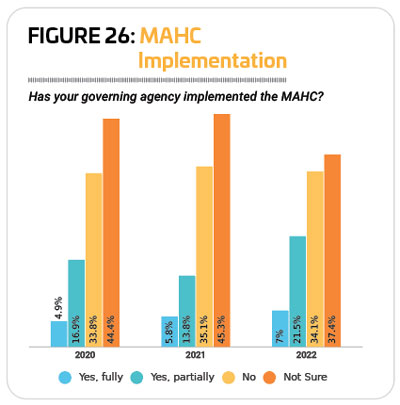

We asked respondents whether the regulatory agency that governs their facilities has adopted the MAHC, either fully or partially. The largest group of respondents to the Aquatic Trends survey—37.4%—were unsure whether their regulatory agency had adopted portions of or all of the MAHC, down from 45.3% in 2021. Also relatively unchanged is the number of respondents who said their agency had not adopted any potion of the code—34.1% in 2022, down from 35.1% in 2021. The number who said their regulatory agency had fully adopted the MAHC increased from 5.8% in 2021 to 7% in 2022, while those who said their agency has adopted portions of the code grew from 13.8% to 21.5%. (See Figure 26.)

Industry Challenges

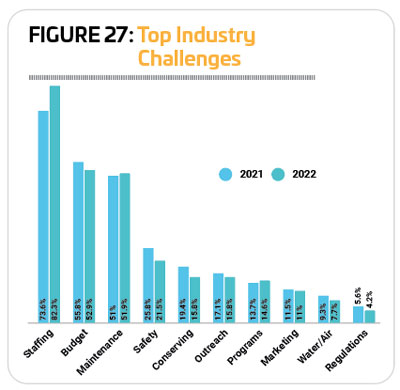

Last year’s report saw a significant jump in the number of respondents listing staffing issues as a top industry concern, and in 2022, even more respondents named staffing as a top concern, with budgetary issues—normally the No. 1 issue of concern—continuing to hold second place.

More than eight in 10 (82.3%) respondents in 2022 said staff ing issues were a top industry concern, up from 73.6% in 2021 and 52.4% in 2020. More than half (52.9%) named budgetary issues as their top concern, down from 55.8% in 2021 and 58.9% in 2020. Equipment and facility maintenance was also named by more than half of respondents (51.9%) as a top concern in 2022, representing little change from 2021 (51%) and 2020 (49.1%). (See Figure 27.)

ing issues were a top industry concern, up from 73.6% in 2021 and 52.4% in 2020. More than half (52.9%) named budgetary issues as their top concern, down from 55.8% in 2021 and 58.9% in 2020. Equipment and facility maintenance was also named by more than half of respondents (51.9%) as a top concern in 2022, representing little change from 2021 (51%) and 2020 (49.1%). (See Figure 27.)

Respondents from Ys, parks and camps were the most likely to name staffing issues as a top concern for the industry. Some 90.2% of Y respondents, 87.5% of park respondents and 86.2% of camp respondents said staffing issues were their number one concern.

In light of the staffing issues that have plagued many industries over the past year, along with anecdotal reporting that lifeguards have been particularly difficult to staff at aquatic facilities, we asked survey participants about their experience with hiring lifeguards. More than two-thirds (67.3%) said that their facilities had been affected by lifeguard staffing difficulties in 2022, while only a third (32.7%) said their facilities were not affected. Respondents from camps were the least likely to report that they were affected by lifeguard shortages, with just 44.4% indicating it was a problem. On the other end of the spectrum, Ys were the most likely to be affected by lifeguard shortages, with 80.3% indicating it was a problem for their facility.

The lifeguard shortage affected operations in various ways. Some 59.3% said they had reduced their hours of operation because of lifeguard shortages, and 16.8% shortened their s eason of operation. Nearly one in 10 (8.4%) said at least one of their pools remained closed for the season due to lifeguard staffing difficulties.

eason of operation. Nearly one in 10 (8.4%) said at least one of their pools remained closed for the season due to lifeguard staffing difficulties.

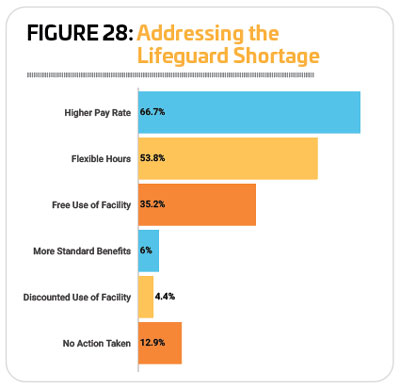

We also asked respondents if they had taken any actions to attract more lifeguards to staff their facilities. Two-thirds of respondents (66.7%) said that they had offered a higher rate of pay to attract more potential lifeguards, and more than half (53.8%) said they offered flexible hours. More than one-third (35.2%) said they offered free use of their facility to attract more lifeguard candidates (and 4.4% offered discounts for facility use). Another 6% said they increased their standard benefits, such as insurance, retirement, etc. (See Figure 28.)

Some respondents offered up other ideas for attracting more lifeguards, including hiring bonuses and free (or discounted) lifeguard certification. Several respondents mentioned working to promote the work culture, describing it as like a “family” or “community” that people would want to join.

Asked about the greatest challenge for their facilities over the past year, while a few still named COVID and its associated restrictions or budgetary issues, a majority cited staffing problems as their top problem. Managing and maintaining aging facilities, along with associated inflationary challenges, were also named as a challenge by a substantial number of respondents, and a handful mentioned chemical or chlorine shortages as well. Several also mentioned difficulties with patrons, from “entitled attitudes” to “unruly behavior,” “big crowds” and more. RM