It was in 1907 that Scouting movement founder and English soldier Robert Baden-Powell devised the motto, “Be prepared.”

More than 100 years later, the idea still resonates, whether you’re an individual looking to head into the great outdoors for a great adventure or you’re a park district administrator, event coordinator or athletic director looking for ways to provide outdoor recreation, sports and fitness while protecting your facilities and patrons from everything from heat waves and hurricanes to icy roads and lightning strikes.

There’s no doubt that severe weather can dampen

(or freeze, flood, burn or blow away) your best-laid plans for outdoor fun, but you can be better prepared to deal with what Mother Nature dishes out, protecting your patrons, players and staff from that fickle lady’s moods and tantrums.

Have a Plan

Whether it’s a thunderstorm, a blizzard or a heat wave, being prepared for severe weather events means having a plan in place. For Germantown, Md.-based AEM, a provider of solutions that help mitigate the risk of extreme environmental events, that plan involves three pillars: analyze, plan, and implement.

“The first thing we ask people to do is to get an inventory of what they’re trying to protect,” said Vice President of Marketing Anuj Agrawal. “Then, ask what kinds of activities are happening there. Is it a school event? A game? Something else?”

Another part of your analysis obviously should involve assessing the prevailing weather in your area. “In the Southeast, hurricanes and lightning are a risk,” Agrawal said. “In other places it’s heat stress. So you need to ask what is it you’re protecting, and what are you protecting it from?”

It can be helpful during this phase of your planning process to speak with a meteorologist or take a look at your area’s historical weather data.

Next, consider any sanctioning body guidelines that are pertinent to your organization. For example, heat stress and the injuries associated with it can be severe. If your local government or high school doesn’t have a guideline in place already for how to manage things like football practice on hot days or how long to keep players on the field when lightning approaches, look for best practices from organizations like the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) or the National Athletic Trainers Association (NATA), AEM suggests.

Finally, take a look at your evacuation protocols and sheltering locations. “We like people to think about how long it’s going to take you to shut down your operations and get people to safety,” Agrawal explained.

Be prepared to adjust your plans depending on the number of people you need to protect. A small ballgame with parents in attendance won’t require as much time as a large festival with hundreds of attendees.

NATA says you should identify the locations safe from lightning in advance of any events. It might be a building or a fully enclosed space, or even a car. Shelters are considered unsafe, as they are partially open to the elements.

Once you’ve all this information down, it’s time to make a plan for how to handle severe weather. This includes establishing policies based on the type of outdoor activity, severe weather variable, season and responsible parties, according to the AEM website. “For example,” it states, “the head of your recreation services should have separate plans for wellness and fitness classes, arts and crafts, and outside sports leagues.”

It adds, “You could create policies for summer, fall, winter and spring seasons, which highlight the associated weather risks with call-outs to specific staff members of implementation responsibilities.”

From here, your plan should include the following: forecasting and detection, alerting procedure, safety protocol during a severe weather event, designated safe shelters, and chain of command. Where are you getting your forecasts or weather warnings? How are you ensuring the right people get alerted when problems arise? Is it an email or text to staff, or do you want to include physical horn and strobe alerting systems?

“Understand when you want to be alerted for certain situations,” Agrawal said. “We monitor lightning in real time. Within 10 seconds of a lightning strike happening, we can send an alert.”

So ask yourself, when do you want to be alerted? And who should get the alert? For example, Agrawal said, if there’s lightning within 25 miles, perhaps an email or text is sent. “When it gets to 10 miles, that’s when most organizations will start to shut things down,” he added. “For something like education or parks and recreation, they’re usually more conservative, so 10 miles out, they get an alert.”

You also need to decide when you want to send the all-clear. “It could be at 10 miles or it could be time-based—30 minutes from the last strike,” Agrawal said. “Basically, you need to get that system in order. Figure out the geography you’re trying to protect, and determine how to place equipment so everyone will be notified.

“Usually, we’ll have managers and supervisors get the initial alerts, but then more of the staff and the people who have to get the safety policy in place will get an alert when it’s 10 miles out.” The system is customizable, so you can decide who needs to be aware, and when.

Once everyone is aware that problem weather is approaching, your safety protocol plan should be enacted. All outdoor activity should cease, and everyone can head to your safe area.

The third pillar—implementation—means taking your analysis and your plan and putting them into action. AEM’s website has a checklist for implementation:

- Identify and install the technology or technologies to support your custom policy.

- Activate alerts against your established protocols.

- Disseminate policies and procedures.

- Communicate with external associations and emergency departments.

- Educate all parties about threats and safety protocol.

- Communicate the chain of command.

- Test, evaluate and monitor.

Build Your Toolbox

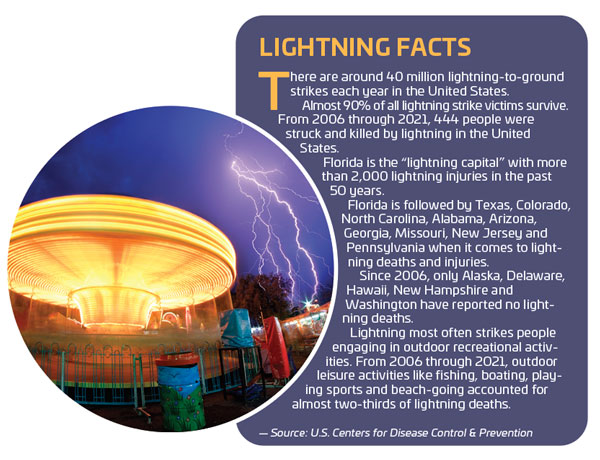

The most common weather events will depend on your location. While hurricanes and tornadoes drive a lot of news reporting, Agrawal said that the most common problems are “lightning, heat stress, cold weather and high winds,” and that “lightning is the No. 1 issue people are looking to solve.”

This is primarily about safety, he said. “How do you keep visitors and employees and student athletes safe from lightning?”

Here, technology can help. Agrawal’s company’s lightning detection system, for example, monitors strikes happening within the clouds, as well as cloud-to-ground lightning. “In-cloud lightning is usually a precursor,” he said. The system also includes a horn and strobe, which alerts everyone when lightning is in the area and outdoor activities must cease. A countdown clock can also be added, so people who are anxious to get back to the activity can stay informed as to when activities can be resumed, Agrawal said.

Other tools you can add include storm tracking software (which might also allow you to set up alerts to staff when bad weather threatens), as well as professional-level weather stations to keep you on top of everything from high wind (so you’ll know when to take down your shade structures) and precipitation (helping you stay on top of irrigation needs for your sports fields) to temperature (so you’ll know you need to cancel that football practice to protect players from heat injury).

You might also look to partner with a company that provides access to a meteorologist. “A lot of people know the weather pretty well, but if you have to make an important decision, a meteorologist on standby can help with that decision-making process,” Agrawal said.

Tools to keep the public informed are another possible tool you can rely on, with a display to let people know when activity needs to shut down and why, as well as when it can resume.

Lee County in Florida installed 23 lightning alerting systems across its pools and parks, along with adding a couple of weather stations.

“They’ve been using this since 2012,” Agrawal said, adding that the county got a lot more serious about lightning threats when an 11-year-old boy was hit by lightning and ended up dying. “They were just using the ‘flash-to-bang’ method, but now they have a more robust method for protecting people from lightning.” RM