For most of our history (and much of our prehistory), human life has been intricately connected with water. Our earliest organized communities arose around lakes and rivers, and we continue to be drawn to the water, from local river trails to beachfront resorts. It’s not just that we need water to live; being in—or even near—is a calming experience that demonstrates our connection with nature.

And now that many manufacturing uses have subsided from waterfronts across the country, communities are stepping in to transform them into recreation destinations of all kinds.

“One of the benefits of looking at opportunities on waterfronts is the perceived beauty and connection, but also, there is research showing that having that connection with water provides a level of calmness. It provides a calming of the senses. It gives you serenity,” said Anna Cawrse, ASLA, PLA, landscape architect and co-director of Sasaki’s office in Denver. “I think we can say waterfront recreation is amazing because it feels good, and there’s actually research out there that proves that’s true. It’s important both for our physical and mental well-being to have that connection to those bodies of water.”

Ryan Hartberg, sales and marketing VP for a Verona, Wis.-based company specializing in recreation products and services, including waterfront development, said there can be many reasons for redeveloping a waterfront. It might simply be to add another amenity for residents, or to provide a programming tool for a diverse range of activities beyond just swimming. It also could be to drive revenue and profitability.

For example, take a community that’s redeveloping an old beachfront property or retired quarry site into a destination location for the surrounding community. “You’re providing an amenity for your residents, and it can be altruistic or also economic,” Hartberg said. Not only are you doing something good for your community, “… you’re keeping residents in your community and also drawing residents from other communities.”

With so many waterfront spaces experiencing some degree of neglect or even outright abuse from past uses, there is also a much larger-scale benefit to bringing them back to life (and bringing the life back to them).

“There’s the ecological benefit of it—creating tomorrow’s stewards,” said Jason Stangland, director of SmithGroup’s waterfront market. “There are many sites that have been previously developed but not respected. That we can help the earth is appealing to a lot of people—every group you’re working with can appreciate that. …There’s an inherent good and value around the premise of restoration, but there’s also this other aspect, which is that it has benefits for us. …We’re part of an ecology. We can contribute or detract, just like anything else. That lens is a motivating factor for a lot of folks.

“The other lens a lot of folks are intrigued about is how the sites create unique opportunities,” he continued. “They’re inherently different. What’s the programming associated with it? Are you getting into the water or next to the water? There’s so many ways you can handle that land-water interface, that recreational engagement interface, and it can be a unique driver of people to waterfront destinations.”

First Steps

Before you can begin work on your waterfront, you need to have an idea about where you’re going. Lead with purpose, Hartberg said. “What is your purpose? That’s your first question. What are you trying to accomplish?” he asked. From there, ensure your purpose is aligned with the needs of your intended audience.

Then consult with a designer experienced in waterfront redevelopment for recreational use, and seek advice from professionals who understand both the engineering and operational modeling for best practices and monetization in the recreation industry, he explained.

“There’s a lot of engineers and people who build things for a living, but they don’t necessarily understand the recreation, the monetization, the investment, budgetary estimates, and so it can take a long time to get to that point with a lot of people compared to somebody who’s been there, done that.”

For many developments, such as camps or small waterfront recreation areas, the purpose might be more obvious, whether it’s providing specific programming opportunities on or near the water, or simply offering active and passive recreation to a diverse audience. But some projects require a bolder vision.

“For many of our cities, water bodies were the reason that a city was developed in a certain region, even going back to indigenous communities,” Cawrse said. “As the decades and centuries have passed, we have a very different relationship with our water bodies. They’ve been choked off by infrastructures, and the water body becomes almost an afterthought” or worse, the place where we deposit all of the harm created by our cities. “So, when a city is coming to think about the future of a water body, I would encourage them to be bold first. A lot of times, being bold and visionary is what’s going to overcome these years of neglect.

… That’s what’s going to allow you to really push the boundaries and make something really beautiful and intentional happen in the future.”

From there, she said, you can zoom out and look for the “connective opportunities that give communities that maybe didn’t have access, access to their waterfront,” while also looking at “not just the edge, but the water system itself. We have a lot of contaminated waterways in our country, from the Ohio River to places like Lake Monona (in Madison, Wis.), and we can figure out some of what’s causing those issues with our water.”

That might require zooming out further than you’d expect, as some impacts to the waterfront—like agricultural runoff—can be wide-ranging.

This kind of approach—improving access to the water for local community members while also improving the ecological health of the waterfront itself—might sound daunting, but it is also one of the best ways to ensure the project can qualify for grant funding, according to Stangland.

“As we start to focus on trying to address the issues and challenges we face at scale,” he said, “they require us to spend significant dollars. …When you make an investment in the community, it’s better to do more things… to address flooding and recreation.”

Stangland called it a Swiss army knife approach, and said that this is the best example of how to ensure your project is grant-worthy. “Recreation, yes. Restoration, yes,” he said. “The more you can tie it to issues of equity, ecology, the human spirit—as long as you can tie it to multiple things, that’s a big component.”

In addition, having a plan in place is critical. “Whether you’re a funder or a regulator, they want to see something that’s been evaluated and tested and has come out the other end with support.”

Amenities & Programming

A waterfront presents a broad range of possibilities when it comes to amenities and programming. Do you simply want to create a riverwalk with some seating and shade here and there? Or do you want to provide an immersive experience with activities on the water and on land too? How do you find what will work best for your site?

“It goes back to that purpose. It goes back to how you’re using it—is this an amenity, a programming tool or a revenue driver? Because the answer then caters to your purpose and your goals,” Hartberg said.

Overall, he said, you should offer a wide mix of opportunities for active and passive recreation in, on and around the water that cater to all ages and abilities. “So it’s nice to have a zipline that’s active, exciting and more of a thrill type of thing, but it’s also nice to have green space, on the other end of that spectrum where people can just lie and relax or bring a picnic basket and have some quiet time or maybe throw a frisbee,” Hartberg said. “And then there’s everything in between, so it could be a miniature golf course or a splash pad. It could be more active like an inflatable aqua park or waterslides. On the other end it could be pavilions and shade—shade’s a big thing, especially in waterfronts, you need a place to sit and recreate and relax, read or eat.”

Access to the water is also a crucial consideration, through a floating dock or even developing a portion of the waterfront to make sure people can easily get to the water.

Madison, Wis., might be a thriving capital on an isthmus now, but its first human inhabitants—the Ho-Chunk Nation—were first drawn to its system of freshwater lakes thousands of years ago, a history that informed the masterplan created by Sasaki for the revitalization and redevelopment of this waterfront.

“That relationship the Ho-Chunk Nation had with the water was one of respect and taking care,” Cawrse said. “We wanted to start with that history as a baseline, so the first amenity to be created is green infrastructure. This involves creating a softer edge along the waterfront, allowing us to capture runoff and pollutants. So it starts with cleaning the lake and giving back to the lake.

“From there, we started to think about what amenities are missing along the waterfront,” she continued. The goal was to complement the opportunities at existing parks. Among the planned amenities are a safe, multimodal path along the waterfront and a series of docks and other opportunities to get into the water. “There’s an incredible fishing community there, with people coming from all over the region to fish.”

Along the lakefront, Olin Park provides a forested oasis, so canopy walks are part of the plan there, with areas to get into the water with kayaks, smaller trails and nature play. And a new park will be developed over the John Nolen Drive with an outdoor amphitheater, a community boathouse and a concession. Importantly, this development will help connect downtown to the waterfront.

Hartberg said that once you’re in the design phase, you should consider your space and your budget to determine how many different opportunities you can provide. “We use the term ‘recreation zones’ or ‘strategic design,’” he said. It goes back to your purpose, your space, your budget and your audience. “So, how many things can I have here? How much space, how many people do I need to serve? If you’re outside of the Dallas metro area it’s one thing, but if you’re in the middle of nowhere, it’s a different number, but it’s about understanding, if I need to take care of this many people, I need to have enough different zones to serve a wide range of people, and then having those distinct zones.”

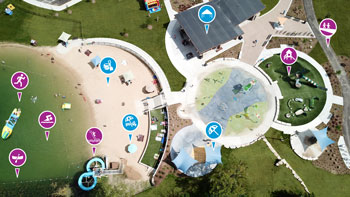

Recreation zones can focus on a variety of opportunities, from aqua parks and zip lines for young and active visitors to pickleball courts for older, active visitors, with plenty of places to relax interspersed, making it easy for people to move from active to passive zones and vice versa. (See Figure 1 on page 20 for an example of how recreation zones can work for a waterfront site.)

“We also talk about circuits,” Hartberg said. “We create a circuit, combining land and water.” While the circuit is created intentionally, for the child playing on the playground, who then rides a zipline into the water, plays on an inflatable aqua park and then swims back to the dock and finds another activity to do, it means a seamless recreational experience. Perhaps more importantly, it “relieves pressure” from any single amenity.

Ecologically Minded

Not every waterfront owner or stakeholder will have ecology front of mind when they begin a redevelopment or

revitalization project, but there are good reasons to keep sustainability in focus. It’s not just about doing “the right thing,” either.

While not every client comes with such a focus, Hartberg said, “if it’s up to us, it’s always important. There’s no sense in creating something that can only last a few years, so trying to create sustainable solutions is always wise so that we can use it.”

And in the long run, he added, it can be a more economical option, as well as a differentiator. “From a business perspective, I can differentiate because not everybody will think about it or take the time to understand it and design it that way and then not be able to operate it that way, so in this world of aquatic centers and aqua parks and things that are manmade, to have something that’s a little more natural—people just seem to like it. Everybody has fond memories of going to camp or jumping in the pond.”

And, he added, when a project is more sustainably developed, it might result in a lower operational cost in the long term.

For Sasaki, ecological sustainability is the “backbone of the project. You have to get that right,” Cawrse said. “We have to put that as the foundation of our project.”

At Lake Monona, that means a team of experts including Andy Sell, a senior project landscape architect and ecologist at Sasaki, who helped the team consider how to approach the water’s edges. In Madison, that means ensuring the edge can handle wave action as well as ice shelves in the winter.

Challenges Met

Waterfront developments can come with a host of unique challenges, so what should you be prepared for? A few common challenges Hartberg said are important to keep in mind include:

- Understanding the water’s quality, depth and safety considerations, along with addressing any logistical challenges such as access and slope.

- Navigating land purchasing, ownership and adherence to local codes and ordinances.

- Conducting thorough operational cost estimates to ensure long-term viability and sustainability.

Cawrse also pointed to potential challenges around the permitting process, adding that sometimes it can take a lot of time and effort to get such projects built. She added that it’s important to have an integrated team that understands all aspects of the project to help prevent any pitfalls. “While I encourage everyone to be visionary, I also encourage them to be really practical so you can get it done,” she said.

Other challenges can be unique to the project. In Euclid, Ohio, on the shore of Lake Erie just east of Cleveland, reconnecting the city to its lakefront to provide equitable access meant working closely with shoreline property owners. The process involved countless meetings, Stangland said, but ultimately a solution presented itself. Erosion control had been an ongoing and costly battle for the property owners involved. By taking on erosion control itself (largely through government funds and grants), the city was able to work out agreements with nearly 100 landowners for rights to develop a public trail and other recreational amenities along the lakefront.

“We came up with the plan, but if you’re going to do this—change the pattern of how people use the lakefront—it impacts the adjacent landowners,” Stangland said. Ultimately, SmithGroup held a series of meetings, speaking individually with lakefront property owners. The existence of a bluffline made it possible to build the trail in a way that would not impact landowners severely, but the more important piece of the puzzle was saving landowners from the high costs associated with shoreline protection.

The plan’s first phase included the Joseph Farrell Memorial Fishing Pier, completed in 2012, which helped demonstrate the communities commitment and bolster the support needed to invest in further development. The second phase involved construction of a ¾-mile lakefront public access trail that parallels coastal structures and new beaches that will stabilize the shoreline. Future phases include a recreational marina, a public beach house for community events and a nature-based playground. Ultimately, the project will link two public lakefront parks, underinvested neighborhoods, Euclid’s central business district and the Lake Erie Coastal Lakefront Bikeway.

“It’s created this momentum that is pretty powerful,” Stangland said. The “model of addressing equitable access and resilience of the shoreline at scale” caught the attention of Cuyahoga County planners who asked, “Why aren’t we doing this across the entire lakefront?” This led to SmithGroup creating a plan that addresses the entire lakefront.

The Lakefront Public Access Plan will cover the entire 32-mile Lake Erie shoreline within Cuyahoga County, and like the smaller Euclid project, it will stabilize severely eroding shoreline while expanding public access to the lake for all residents. Lakefront landowners will grant easements for a public lakefront trail in exchange for erosion control provided largely through government funds and grants. Ultimately, the plan will increase public access to the lakefront by more than 50%, and more than 300% outside of downtown Cleveland.

“One of the biggest challenges we faced is that those projects involve somebody else’s backyard,” Stangland said. “I have to make you as the landowner comfortable, so I’m prioritizing your concerns and motivations, but I have a bunch of other people in the general public who also have to comment. So when you’re working on a project that broaches public-private partnership, you have to know there’s a very real, individual level of dialogue that has to happen with private landowners. You want to be inclusive and make it a public process, but at the end of the day, if ‘Joan’ and ‘Charlene’ aren’t comfortable, the project won’t move.”

Take Your Time

If you find that the main challenge with your waterfront project is simply the scope of the thing, you can take comfort in knowing that though these projects can be vast, they can also be brought down to scale and built in phases.

“Consider modular development starting with a master plan and expanding over time,” Hartberg said. “Start with strategic ‘anchor amenities’ to drive revenue” and then use that revenue to help you develop an additional phase of your master plan every year. “For those who are more risk-averse or have constrained funding availability, there are models that allow you to start with smaller-scale projects and gradually scale up based on demand and resources.” RM