According to the latest information from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), more than one in four adults in the U.S. reported having a disability in 2022. And that number grows with age, with 43.9% of those 65 years of age and older reporting having a disability.

Signed into law by President George H.W. Bush on July 26, 1990, the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) is a civil rights law prohibiting discrimination against those with disabilities in a wide range of public areas, from employment and schools to transportation and public (and some private) places. Under the ADA, accessibility standards that apply to places of public accommodation, commercial facilities, and state and local government facilities are based on minimum guidelines set by the Access Board, which not only sets these standards but also provides technical assistance and training on the standards.

We often report on the latest developments in inclusive playground design on these pages—including the importance of going beyond the requirements of the ADA to provide true inclusivity, where people of all abilities can play alongside one another. But parks are more than playgrounds, and there are other types of facilities—swimming pools, ballfields, fitness clubs, and more—that can benefit from finding ways to improve inclusion and accessibility. After all, a quarter of potential adult visitors could potentially face barriers and need some kind of accommodation to enjoy the social, health, and other benefits of engaging in swimming, sports, recreation, and fitness. And if you’re aiming to serve the aging population—and more than half (52.4%) of respondents to the 2024 Industry Report Survey said they provide programming for older adults—ensuring inclusion is a smart strategy for expanding your programs’ reach.

“There are many benefits to accessible facilities,” said Allison Abel, marketing director for a California-based outdoor fitness equipment manufacturer whose lineup includes many accessible options. “First and foremost is the enhanced quality of life for those who might not otherwise have the opportunity to enjoy certain facilities or programs.”

Community cohesion is another benefit, she explained. “When facilities are made more accessible to those with mobility impairments,” for example, “it encourages them to participate more fully in activities outside the home, thus facilitating new social connections and thereby strengthening the fabric of local communities.

“In addition,” Abel added, “accessible amenities will make for higher ROI on investments in facilities when they generate greater overall usership.”

A focus on inclusion in your facility goes beyond design principles, according to Marley Cunningham, director of marketing for a Missoula, Mont.-based company that designs and builds recreation, fitness and ability-enhancing equipment. “It’s a declaration of belonging,” she said. “When we create spaces that are truly accessible and welcoming to everyone, we empower individuals to fully engage with their communities, regardless of their abilities, backgrounds, or identities. The benefits ripple outward: Accessible facilities promote physical health, foster mental well-being, and build a sense of connection. They transform what might be a simple building into a hub of unity.”

Your efforts to build inclusivity into your facility will also reap the benefits of long-term loyalty, Cunningham added. “When patrons feel seen, valued, and accommodated, they’re more likely to return—and to recommend your facility to others,” she said. “It’s about fostering an environment where everyone feels welcome, from the moment they walk through the door. And that’s not just good for people; it’s good for business. By embracing inclusivity, facility owners unlock the potential to build a space that thrives both socially and financially.”

What’s Stopping You?

So what are some of the challenges and barriers that keep facilities from improving their accessibility and inclusiveness?

“There can be several different barriers, but I think a few common ones are overall cost, landscape, and knowledge of what is inclusive and accessible,” said Kristyn Young, director of planning and marketing for a Minden, Nev.-based manufacturer of restroom structures. “Cost is always a factor in every project, and sometimes including new features or adjusting the landscape (grade of sidewalks, etc.) can be challenging. But if there is a way to do it it’s a worthwhile investment in your community.”

Abel agreed that one significant challenge is simply the “…lack of awareness among project planners regarding the wide range of accessible options available for various amenities.” She added that “this lack of knowledge can result in missed opportunities to incorporate designs and equipment that could better accommodate individuals with disabilities, ultimately limiting the inclusivity and usability of the spaces being created.”

Young agreed, “From a design standpoint, I think sometimes it’s just understanding certain features and what they really provide. For example, adult changing stations and incorporating private, family restrooms are seen as maybe unnecessary, but they really make a huge difference for those who are faced with that reality. Going beyond the bare minimum of what is required and thinking about the end user and how they experience your new park [or facility] is really the mindset one should have.”

When discussing barriers to inclusivity, we often first think of physical obstacles, like a lack of ramps or doorways that are too narrow for a wheelchair to pass through, Cunningham said. “And while those are important to address, one of the biggest barriers we face is less visible but just as impactful—mental barriers.

“The idea that ‘we’ve never seen a wheelchair user here, so it must not be needed’ is unfortunately something we still often encounter in the field,” she added. “But that mindset misses a critical point: People don’t show up when they don’t feel welcome or when they know they won’t be accommodated. Inclusivity isn’t about responding to who’s already here; it’s about creating an environment where everyone feels they belong. It’s proactive, not reactive.”

Cunningham added that another such mental barrier is the idea that only a small number of people can benefit from inclusivity. “The truth is, features like accessible seating, sensory-friendly spaces, or diverse programming benefit everyone,” she said. “Take a parent pushing a stroller, an older adult with arthritis, or someone recovering from surgery—these individuals all gain from inclusive design.

“And let’s not overlook social barriers,” she continued. “Sometimes the lack of diversity in marketing materials or staff training can send unintentional messages that a facility isn’t for everyone. Overcoming these barriers requires a shift in perspective, one where we see inclusivity not as an added expense but as an essential investment in our communities and our humanity.”

Parks Are More Than Playgrounds

Inclusive playgrounds have been a popular topic in these pages and at recreation conferences for the past decade, and though there’s always more that can be done, much progress has been made on manufacturing equipment and designing play areas that are truly inclusive. But parks are more than playgrounds. Designing and installing an inclusive playground should go hand-in-hand with assessing the rest of your park site, and determining how to extend your goal of inclusion throughout.

“By making parks more inclusive and accessible, you truly are designing for all individuals within the community and incorporating elements that might otherwise be overlooked,” Young said. “By incorporating restrooms and playgrounds that are designed for individuals with different needs, you are actively welcoming those individuals to come to your new park and making it a ‘highlight’ of the park—instead of just becoming another park.”

“One of the greatest barriers to inclusivity is the misunderstanding of the distinction between ADA compliance and accessible recreation,” Abel said. “As a result of the Americans with Disabilities Act, facilities now include accessible parking lots, travel routes, and restrooms—and possibly accessible picnic tables. These steps to provide access to the facilities themselves are a great initial step. However, when it comes to providing ways for those with various disabilities to engage in recreational activities, the options at many facilities may be limited or even nonexistent.

“Project planners can increase inclusion in their facilities by surveying community members for what will be valuable to them and their households, to make sure funding is spent in such a way as to benefit the greatest number of people,” she added. “Some facilities by their very nature will be more naturally accessible than others. Facilities that can easily be made to accommodate wheelchair users, for example, are outdoor gyms. In many instances these amenities are already inherently inclusive in the sense that they can accommodate a wide range of age levels; ensuring that they include wheelchair-accessible equipment is the natural next step.”

Paralympian and Inclusive Play Specialist Jill Moore offered a number of recommendations for taking inclusivity beyond the playground, suggesting first and foremost that universal design principles are applied to the project. The first of those principles is equitable use, which means “as many people as possible can use it.” Surfaces and pathways are crucial areas of attention for ensuring equitable use. “For example,” she said, “I went to a park with a beautiful complex, including brand-new bathrooms, concession stands and parking, but no pathway between all of them. As soon as you do that, you take away that equitable use factor.”

Here again, going beyond mere ADA compliance helps create equitable use. “If we think about an ADA-compliant sidewalk, it’s 3 feet wide,” Moore said, which accommodates a person in a wheelchair, “but if they’re with a family or with a group, they need more space.” Someone with a service dog or walking with a cane can also benefit from a wider pathway. “There are little things we can do to improve circulation while making sure to make that equitable.”

Flexibility in use is the second principle of universal design. Moore said an example might be putting in hand dryers at different heights, or providing a universal changing table. “Even if you have a kid who needs that that’s 10 years old, they need that additional space,” making the more flexible option (a universal changing table, rather than a baby-changing table) the more inclusive choice.

Simple and intuitive use, and

perceptible information are the third and fourth principles of Universal Design. “I like to use these as a lens for how we look at the overall environment,” Moore said. “This ties in with how people take in information. If you have someone who is blind or low vision, they need color contrast. For example, to see handrails, they need them to contrast with background colors or we’re rendering them useless.”

As another example, she said that relying on Braille for people with visual disabilities will leave out the majority of users. “Only 8% of people with visual disabilities can read Braille,” she said, and of people with a visual disability, “… only 2% is 100% blind. Providing good contrast is helpful to everyone.”

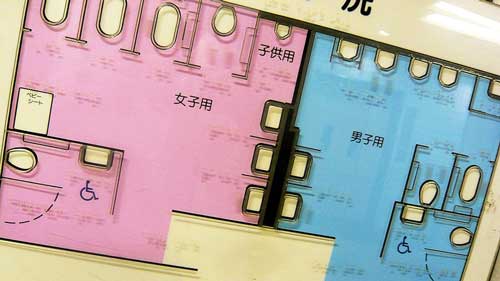

As an example of good intuitive design, she showed a map from Japan of the inside of a restroom. “If you think of a public restroom, you might have to touch a lot of stuff to get where you’re wanting to go” if you have a visual disability. The maps include Braille as well as tactile contrast, helping those users get around. Similar tactile maps placed at a park’s entrance kiosk can help visitors with vision challenges “mentally map” the park’s various amenities.

Of course, not all disabilities are physical. Around one in six children in the U.S. have a developmental disability, according to the CDC, including autism spectrum disorders, speech or language impairment, hearing impairment or hearing loss, and others.

Moore pointed out that those with autism, dyslexia or Downs syndrome, as well as other disabilities, struggle with nervous system and emotional regulation. “When we are growing up, we first rely on co-regulation. We rely on the caregiver to come in, cool us down and use their energy to help us regulate,” she said. But over time, we learn self-regulation strategies. “Some cool things I’ve been seeing are having things be regulating throughout the space,” she added. “It could be a shady spot with some interesting sensory input, maybe a tactile wall nearby. It will physically cool their body stress down and let them self-regulate so they can stay at the park.”

Sensory pods have popped up at sporting events and even music festivals, she said, providing assistance not just for kids but also for adults who get dysregulated.

Restrooms can be another challenge for visitors with disabilities, Moore said. She said when you’re considering the inclusiveness of a park or playground, you should ask three questions: Can you get there? Can you play there? Can you stay there? “This method has been around and spoken about for a while, and I think the ‘staying there’ aspect tends to be challenging,” and this is where restrooms come into play.

If you’re bringing an older child to the playground or splash pad, for example, and the restroom doesn’t include universal changing tables, your options are to change the child on the restroom floor, or perhaps in the backseat of the car, or to simply go home. “That’s a real challenge,” Moore said, “especially for paraplegics. We don’t get a lot of control with restrooms. We can’t get in because the doorway is too small, or there’s no path to get there.

And if the parking and restrooms aren’t good, I don’t want to go.”

Young suggested parks that are aiming for more inclusivity should make sure “… there is at least one if not several ADA-compliant restrooms, but even better is an ADA-compliant, family restroom that offers an adult changing station and privacy.” She added, “Having a private, lockable space to dress and assist another with

a disability is always the best option, as it provides security and peace of mind for both the individual and the caregiver.”

She added that this also helps address gender inclusivity. “Opting for restroom buildings that incorporate single-occupant restrooms is better than multi-occupant restroom layouts,” Young said. “This addresses any privacy concerns for all guests, and doesn’t discriminate against anyone.”

Comfort and the potential for fatigue are other areas where Moore said more attention should be given. “If we have people with disabilities who are susceptible to heat-related illness or fatiguing quicker,” then a focus on creating minimal fatigue is important. That might include shade throughout the park to help visitors keep cool (important for visitors who can’t regulate heat, common among those with spinal and muscle disabilities). In addition, inclusive amenities should be located in areas that can be accessed without creating fatigue. “If I’m exhausted trying to get from point A to point B because of a hill, it’s not going to be any fun,” Moore said.

There are also some fairly easy fixes. “Accessible picnic tables should be connected to the path,” she added, citing an example where an accessible picnic table was purchased, but with the accessible portion of the table on the opposite side from the paved trail. All that needed to be done to improve the site’s accessibility was to rotate the picnic table 180 degrees.

Aquatics for Everyone

In 2010, the ADA Standards for Accessible Design were revised to address swimming pools, setting minimum requirements for making pools and spas accessible, by including pool lifts or zero depth or other accessible means of entry. But that was just the beginning of ensuring aquatic facilities are more inclusive. Just as with playgrounds, attention is being focused on this area.

Kevin Post, chairman and CEO of aquatic design and consulting firm Counsilman-Hunsaker, believes that aquatic facilities built in the coming years “… will increasingly adhere to universal design principles, ensuring that all users, including those with disabilities, can fully enjoy the facility. This might include accessibility ramps, shallow-entry pools, and adaptive swim programs. Inclusive programming will be a design consideration, with features such as sensory-friendly spaces for individuals with autism.”

Cunningham agreed. “At its core, inclusivity is about fairness and equity,” she said. “It’s about recognizing that everyone deserves the same opportunities to play, explore, and thrive. When someone walks into a facility and sees that their needs have been considered—whether it’s a pool lift, a wheelchair ramp, sensory-friendly areas, or signage in multiple languages—it sends a powerful message: ‘You belong here.’ And when people feel they belong, communities grow stronger, healthier, and more vibrant.”

She added that it’s not just the right thing to do, but also a smart business decision. “When facilities are designed to be accessible and inclusive, they naturally attract a broader audience of clientele,” she said. “This means higher patronage, increased attendance, and more opportunities to grow revenue. For example, inclusive programming, such as low-impact water aerobics, serves a diverse group of people: individuals with injuries or mobility impairments, our aging population, and even those looking for a gentle way to ease into fitness. These classes are often in high demand, bringing in consistent participation and helping facilities stand out in their community.”

Post also emphasized adaptive and inclusive programming as a likely trend in the coming years. “As inclusivity becomes a priority,” he said, “aquatic centers will offer specialized programs for people with disabilities, including adaptive swim lessons, sensory-friendly swim times, and therapeutic water activities for those with mobility or developmental challenges. Waterparks may create quieter, less stimulating experiences for guests with autism or sensory sensitivities.”

No Park or Pool? You Can Be Inclusive Too

Improving inclusivity isn’t just a job for parks and playgrounds, or for aquatic facilities aiming to expand their audience. Other kinds of facilities, from sports arenas and ballfields to fitness clubs and recreation centers, can also take these lessons to heart and create a more inclusive environment.

“In fitness centers, adaptive equipment such as hand cycles or machines with adjustable resistance can accommodate people of all abilities,” Cunningham said. “Clear signage, tactile indicators, and open floor plans are also essential for creating spaces that work for everyone, including those with visual impairments.”

Recreation centers and facilities can also take steps toward improving their inclusivity, Cunningham said, adding that they could benefit by “…offering sensory-friendly hours, quiet zones, and staff trained in disability awareness and cultural competency.

“Programming can also play a huge role—adaptive sports leagues, low-impact fitness classes, or family friendly activities designed with inclusivity in mind ensure everyone can participate and feel welcome,” she added.

“The most important thing to keep in mind is that inclusivity isn’t just about infrastructure; it’s about mindset and intent,” Cunningham said. “Facilities can improve their approach simply by listening to the community they serve—inviting feedback from diverse groups and responding with meaningful changes. By combining inclusive design with adaptive programming and intentional outreach, these venues become places where everyone can thrive.

Spread the Word

One last barrier to accessibility is an easy one to knock down. Once you’ve created a more inclusive space, let people know about it.

“When accessible recreational facilities are provided, lack of awareness on the part of the intended users can be an additional barrier,” Abel said. “People in wheelchairs or with disabilities are often not aware that there is equipment specifically made for them in parks and public spaces. It’s important to get the word out about amenities that are available in communities.”

Finally, Cunningham said, understand that “…inclusivity is not a one-time project or a box to check—it’s an ongoing commitment to growth, understanding, and empathy. It’s about asking, ‘Who’s missing here?’ and then doing the work to ensure they feel welcome.

“Inclusivity transforms facilities from mere spaces into true community hubs, where people from all walks of life can connect, grow, and thrive together. And the best part? When we create environments that work for those who need the most support, we end up improving the experience for everyone.

“So, whether you’re a facility owner, a designer, or simply someone who uses these spaces, I’d encourage you to think beyond the obvious. It’s not just about ramps and signage—it’s about fostering a culture where everyone feels seen, valued, and included. That’s the kind of legacy that truly makes a difference.” RM